Red Letter Problem

The role of the gospels in the New Testament

By Scott Canion

Photo by Susan Holt Simpson on Unsplash

We have a red-letter problem.

The red-letter edition of the New Testament was originally conceived of in 1899 by a German immigrant named Louis Klopsch, then an editor of a small Christian newspaper. Klopsch quickly went from editor of that small paper, to owning his own print shop. The story goes that while composing an editorial, his glance happened to fall on a verse in Luke 22 “This cup is the New Testament in my blood, which I shed for you.” A sudden idea came to him that perhaps the words of Jesus should be printed in red, in our English bibles. He discussed the idea with a good friend and mentor who encouraged him, saying… it couldn’t do any harm and could potentially do a lot of good.1

But has it done no harm?

One of the obvious results of red-letter editions is that they have helped cement the idea that the Gospels, and in particular the words and teachings of Jesus contained in them, are the organizing center for the New Testament; and that the ministry patterns of Jesus we find in them are the biblical model for the church’s life, ministry and mission. Some English translations even employ quotation marks, as if the gospel writers were merely stenographers recording dictation from Jesus, and filling in the gaps as best as they could remember.

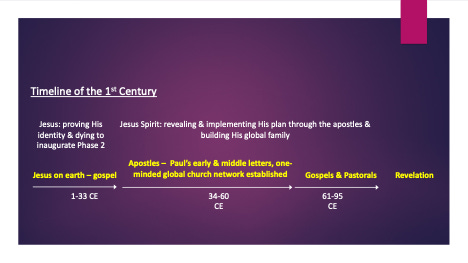

The problem with thinking that way is that the Gospels weren’t pulled together as written documents until near the end of the first century. Quite a lot had happened by the time their authors sat down and carefully organized these biographical narratives. Most of the events recorded in the book of Acts and nearly all of Paul’s letters were written by then, a network of churches had been established across the known world of that time, and Paul was hoping to move to the edge of the Roman Empire and even beyond. If what the Gospel authors recorded was critical for the early life and expansion of Jesus’ church, then why did they wait so long to compile their narratives? And how was so much accomplished in the church prior to having the written Gospels?

The simple answer is that the Gospels are not trying to establish the words and acts of Jesus as the framework for establishing churches. In other words, Jesus came to accomplish something unique and specific, proving who He was, preaching about His coming kingdom, then dying and being resurrected to initiate a new and unanticipated Phase 2 of God’s plan. When Jesus was here on earth He did not provide a model for the church to follow. He did not reveal his grand strategy. He explicitly said His Spirit would teach His followers “everything else” after He went away (John 14:26). Luke picks up on this when he emphasizes, in his two-part work, that his gospel contains “all that Jesus began to do and teach”, while Acts contains all that Jesus continued to do and teach by His Spirit, through the apostles and in His church. The Apostles teaching then, is the “everything else”, the rest of Jesus’ teaching; and Paul was the key apostle to take that new teaching and shape it into a global family movement of churches who were able to process their lives, and the world around them, through an entirely new perspective, a new way of thinking and living. New Testament scholar and theologian N. T. Wright refers to this as Paul implementing what Jesus inaugurated.

“So, though you could say that Paul was picking up this task from Jesus himself, Paul was engaging in it in a new way. Jesus had not tried to generate and sustain a Jew plus Gentile community. He had not, as Paul said he was doing, been taking every thought captive from the wider Gentile world to obey the Messiah. Paul was implementing something which Jesus had accomplished and I'm suggesting that part of that implementation was precisely the developing and urging of this activity of learning to think in the Messiah.”

– N. T. Wright from Why and How Paul Invented Christian Theology

Jesus hand-picked Paul in dramatic fashion, spent significant time directly instructing him (Gal 1:11-21; 2 Cor 12:1-8), and then commissioned him to unveil and implement His grand strategy throughout the gentile world (Eph 3:8-10), so that His churches, in every time and culture, would follow these patterns perpetually until He returns. The Gospels, then, were written after the gospel (kerygma) had gone out across the Roman world and was making its way to the uttermost parts. Paul and his team had established networks of churches that spanned that Roman world. Paul understood his stewardship strategically and comprehensively. He believed that by the end of the first century, he had set in order Christ’s plan, and had accomplished the commission given to him by Jesus, laying out the patterns, processes, principles and practices that should shape the church and its mission until Jesus returns (2 Timothy 4:6-8). To accomplish that, Paul put together and sustained a large team of leaders, coworkers and benefactors, and together they established, maintained and continually expanded a world-wide network of one-minded churches. (We know the churches remained faithful to The Way at least up to the time of Tertullian, nearly 150 years later, as he makes clear in his Prescription Against Heretics, and probably well into the 3rd century.)

The gospel (kerygma) is different from the written Gospels. The gospel is the announcement that Jesus, the Messianic King, has arrived in the middle of history (not at the end as Israel had expected) and brought to completion Phase One of Gods plan (centered on Israel and the law of Moses) and introduced an unanticipated Phase Two of that plan (centered on His global family and the law of liberty). And that one day He would return to gather all His people together to live in a new redeemed society, in a remade heaven and earth. The implication of course, is that those who are part of this new global family He is building, begin living in light of this new reality right away, which brings forward a portion of that new creation into the existing one. To accomplish this, Jesus specifically commissioned Paul to enact His rollout plan for Phase Two so that His churches would understand Jesus’ traditioning pattern for taking the gospel to the uttermost parts of the earth and establishing gospel-communities there. Things started off well enough, but by the 4th century the church got sidetracked by the attractiveness of a culturally dominant version of Christianity (Christendom) which peaked at various points along the timeline (which peak you prefer depends on your theological tradition), but continued as the predominant institution and shaper of Western culture up through the 20th century. The Western church is only now beginning to rediscover bits of the plan Jesus handed off to Paul. If we aren’t careful to recover his traditioning process (keeping our biblical interpretations within the topos framework2 they were written in), we will end up just incorporating those bits into our existing institutions, mashing them together to create something that seems like the rational next step, but still misses Christ’s plan. In other words, we could end up just applying the rules-based system of Phase One to creating our strategies for Phase 2, and decades or centuries from now, we will end up back in the same place that we are today, locked into the rules and procedures of our institutions.

What did the early churches have that made them so different from us? What did it mean for them to devote themselves to what the apostles were teaching? The apostles were training them to reason from the gospel so that they could address situations and solve problems in their situations, living together as families in the new reality Jesus inaugurated. This is fundamentally the format of Paul’s letters. He brings the gospel to bear on a particular situation a church is facing, without giving them sets of rules or formal theologies. This was intentional on his part. This is what it looks like under the new “law of liberty” that Jesus had inaugurated.

Paul was teaching the churches to think Christianly. As Wright aptly said, this is not what Jesus was doing when he was here. Jesus’ goal was not to shape a Jew + Gentile community during his time on earth. He intentionally left that to happen by His Spirit. If we miss this, we miss Christ’s plan. If we miss this, we will attempt to build everything on top of the Gospels, rather than on Acts, with the Gospels coming at the end to reinforce everything that His Spirit had already accomplished through the apostles, particularly Paul.

“He said the Spirit would teach (didache) them everything and remind them of everything He had said to them so far. He was very specific — “He will take what is Jesus,” and declare it to them. The Apostles’ teaching, then, is Christ’s teaching. Jesus said the Spirit will take what is His and declare it. Where is this teaching found now? In the writings of the Apostles (and their co-workers).” – From Jesus to the Gospels by Jeff Reed

By skipping over the activity of the first century and jumping to the Gospels – which even though they contain events from an earlier historical period, were written as a reflection and reinforcement of how the accomplishments of the Spirit during that century were a continuation of what Jesus started – we miss the vocation that was critical to shaping this new community, the church, without which, they could not effectively be the community Christ intended them to be.

“I am talking here primarily about an activity, a vocation, a task and exercise not in other words about the content of a dogmatic syllabus. I am arguing here, as in Paul and the Faithfulness of God, that Paul engaged in and reflected upon and did his best to inculcate in his hearers, an activity which he believed was vital for the health and witness of the church. What he wanted was that followers of Jesus would in principle be learning to think in a new way. This is of course at the heart of what some today refer to with the word apocalyptic. Paul believed that in Jesus, Israel's Messiah, and supremely in His death and resurrection, Israel's God had unveiled his new creation. He believed that Jesus’ followers were called to be part of that new creation and that that meant a new kind of thinking. The content of the thought of course mattered vitally but learning to think in the new way mattered above all and for Paul this vocation, this activity, which I loosely call Christian theology, was load-bearing. Without it the church would not be, could not be what it was called to be.” – N. T. Wright from Why and How Paul Invented Christian Theology

Misunderstanding the relationship between Acts and the Gospels has caused Christendom to build on the wrong foundation. Besides shaping the entire discipleship movement of the twentieth century, the misappropriated emphasis on the Gospels also became the starting point for most Western mission agencies and Christian relief organizations. We have even shaped media and film around this reverse emphasis. One current example is The Chosen television series. Anecdotally, the amount of devotion its followers give it goes beyond what seems reasonable for a television show. The Chosen is a well-produced, moving, historical-fiction production based on events recorded in the Gospels. [I am not knocking The Chosen. I’ve enjoyed the first four seasons quite a lot.] But because it contains imagery and language of Jesus it gets the “red letter” treatment and is used as a teaching tool in churches and Christian ministries and discipleship organizations. New and not-yet believers are being uncritically catechized in the messages of the show, rather than in the gospel itself and the patterns from Acts (which is what the first-century Christians were catechized in). It’s difficult to say just how widespread this practice is, but it’s observable in many contexts. I’m not saying that artistic media about the life of Jesus is inherently a bad thing, and I’m not calling out The Chosen as more extreme than other examples, its just one of the more prominent ones. However, when you combine all the various cultural contributors, they create a way of thinking that overlooks the patterns in Acts.

They miss Jesus’ plan for churches and jump right to the Gospels without going through the same process that the early church and the Gospel writers went through, thereby missing what the Gospel writers are trying to do and say.

Art and media are powerful tools and can be used to great effect. Whether that effect is beneficial or not, to large degree, depends on how accurately the art reflects Christ’s plan and the emphases of the New Testament. My concern is that much of the media, curriculum, and organizational emphases created in Western Christianity have missed Christ’s plan and replaced it with randomized bits of the Gospel accounts, missing what the Gospels are actually there to accomplish.

We need to understand the Gospels as reflections on

the gradual implementation of Jesus’ plan through the apostles,

going from a small, spontaneous (and mostly Jewish) band of followers in Jerusalem

and emerging at the end of the first century,

as a unified global family made up of both Jews and Gentiles.Rather than using the Gospels as the organizing center, we should be thinking of them as capstones on the New Testament – biographies of Jesus, that after decades of Christ’s plan being carried out, after a global network of one-minded churches was established, and much theological reflection had taken place, were written to help the church view what Jesus began when He was on earth through the lens of what His Spirit accomplished through the apostles during the first century. It’s like a filmmaker, who after telling their story through a series of films, goes back and adds a prequel to fill in that understanding (making it richer, clarifying the big picture and stregthening the overall story), but who has the luxury of having the body of the story already recorded. We need to understand the Gospels as reflections on the gradual implementation of Jesus’ plan through the apostles, going from a small, spontaneous (and mostly Jewish) band of followers in Jerusalem and emerging at the end of the first century, as a unified global family made up of both Jews and Gentiles. The Gospel writers came to understand that this was Jesus’ plan all along and they were able to reflect back on the eyewitness accounts (their own and others’) and understand them through that perspective. Collectively they wrote over a period of about 25 years, with specific purposes in mind, for specific communities.

Here is a representation of their significance, in the order they were written:

1. Mark: Announcement of the new community 2. Matthew: Proclamation that Jesus will build His church

Addressing Peter’s Ministry Context: Jewish believers being introduced to Jesus’ new global family 3. Luke: All that Jesus accomplished – Part 1 (with Acts as Part 2, all that Jesus continued to accomplish by His Spirit, through the apostles, in His church)

Addressing Paul’s Ministry Context: Building a unified Jew + Gentile community around Jesus’ revealed master plan 4. John: That the world will know we are one

Addressing John’s Ministry Context: Maintaining one-minded unity of life and purpose in the churches, so that they remain faithful until the end, as the unified global family of Jesus Obviously, I’m using the red-letters and The Chosen as proxies to represent the prevalent misunderstanding that the Gospels are the organizing center of the New Testament.

My conclusion is that the red-letter phenomenon and its associated cultural emphases are a distraction that permeates much more than just our devotional reading of the New Testament. What we really need is to locate and recover Christ’s grand strategy3, which includes that new way of thinking that Paul so carefully laid into the first century churches, through his visits, letters, sending team members and coworkers, benefactors that funded the work, and through the leaders that were appointed in each church, who could continue maturing and expanding the churches, so that they would be able to use the gospel flexibly in their situation, rather than just following a prescribed set of rules, or attempting to intuit a new set of rules using cultural priorities or human logic.

We need revival, but not the kind that ends in tears, the kind that ends in “churches that are strengthened and multiplied regularly” (Acts 16:5). We need revival of the mind. We need a new paradigm. We need an Emmaus road experience, having our eyes opened to God’s eternal plan and our part in it. We need a complete reorientation of our entire lives and perspective, which is exactly what Paul is calling for in Romans 12:1-2. We need to return to the patterns and compelling vision from Acts (All that Jesus accomplished - Part 2).

Scott Canion is based out of the NYC area and is part of the METRO equipping team, a network of global leaders who are establishing churches that are families, patterning themselves after Acts.

From The Story Behind: Red Letter Bible Editions by Steve Eng (Bible Collectors’ World – Jan/Mar 1986)

A topos (or topoi plural) are terms that refer to literary formulae that carry a set of organizing ideas, which set the context for understanding a passage or an entire essay. They carry familiar traits that allow a reader to recognize what type of passage they are reading and they provide an entire fraework for understanding and engaging with a passage or essay. One such example are the household texts in Eph 5-6, Col 3-4:1, 1 Pet 2-3 and Paul’s later letters to Timothy and Titus. If the reader doesn’t recognize that they are reading a household text, or understand the organizing framework of that particular topos, then they will misunderstand the meaning of the author in that passage.

Jesus’ grand strategy refers to the idea communicated in Ephesians 3:10, where Paul states that Jesus gave him a unique stewardship to do two things: make known Jesus’ master plan or grand strategy for His unfolding kingdom and to initiate that plan in a way that specifically brings Gentiles into Jesus’ global family and unites that family as one, both Jews and Gentiles.