This Year At Christmas

A response to the "nativity as protest art" installations displayed on the lawns of Catholic Churches across America

Photo by Dan Kiefer on Unsplash

[Stick with me for a minute as I lay some groundwork. I promise this is all leading to my thoughts on “the nativity as protest art”.]

Leveraging special interest groups to create a support base isn’t a strategy exclusive to 21st century American politics. It’s been around for a while.

In 312 CE Constantine the Great had an epiphany which convinced him that the God of the Bible would be his ally in all future military endeavors if he would emblazon Christ’s name on all his armor and outfits. Constantine, being a forward-thinking entrepreneur, designed a line of merch, inventing the graphic tee. These promptly sold out because he hadn’t properly anticipated demand and wasn’t quite ready to go to scale. So, he pitched his idea to the Sharks, garnered some support and rolled his initial success into an Empire-wide chain of Christian gift shops, with their own line of holiday tchotchkes (Christmas ornaments and the like), and then used that success to gain the popular support of the Christian church, eventually building an entire legal infrastructure around it and voila… Christendom and capitalism were born. And they’ve been twinning it ever since.

Okay, that’s not exactly what happened, but it captures the essence of it.

Well, it at least captures some of it.

Okay, it’s embellished quite a bit.

In the early 4th century, the Christian church was still largely a movement of believing communities who shared a common life together for the purpose of building one another up and “seeking the welfare” of their cities; relying on the apostles’ teaching as the body of teaching around which they based their lives; and who shared their resources network-to-network via the apostolic teams who moved among them, helping to create one-minded solidarity, while meeting the pressing needs across the movement… and solving crimes. (No, the apostles didn’t actually solve crimes, but what if they had? Wouldn’t that have made an awesome Netflix1 pulp series?)

Constantine seems to have recognized the potential of these Christians as a significant “special interest group”. Their numbers had gone from about 1,000 followers of Jesus in the mid-1st century, to nearly 9 million by the early 4th century, and he took advantage of that. (I can’t speak to Constantine’s motives, just to where it all led.)

Initially just a pawn in this game of thrones, Christianity eventually landed in the driver’s seat, becoming mostly identified with the “official” institutional church, which began staking its own claim for power and influence within the empire. The road that led Christianity to this point began with a slow departure from the original plan of Christ, around which the early movement of churches had been intentionally shaped by the apostles and their teams. Even before the 4th century the churches had begun falling into the trap of trying to be “culturally relevant”.

“By falling into the trap of trying to make the churches more palatable to both the Roman and the Greek audience, the churches sold their birthright, if you will, turning in “the way of Christ and His Apostles” for a “better” way—which led us on a journey through Greek Orthodoxy to Roman Catholicism, through fundamental Protestantism to modern day liberalism—a journey eventually leading to the death of Western Christendom.”2

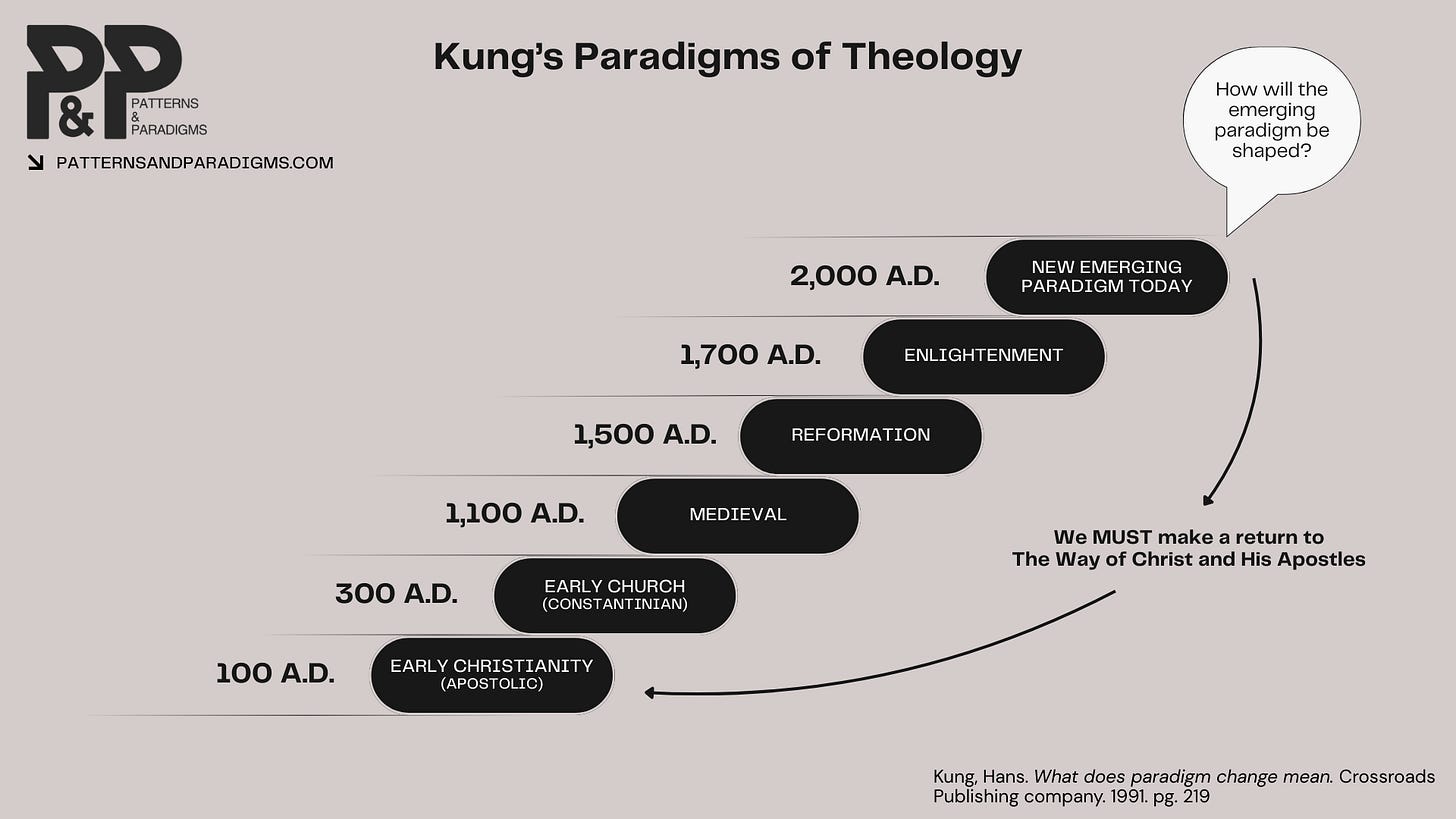

Hans Kung has written extensively on Christian paradigms and has outlined the major paradigms of Christianity over the centuries. Below is a summary of his thoughts.

[Chart from Why Paradigms… and How Did We Get Here by Matthew Andersen]

When Jesus arrived on the scene, he intentionally went around shaking up the old Jewish paradigm and introducing a new way of understanding all that God had been doing up to that time. Then Jesus handed off, to Paul and the other apostles, the task of making sure that his plan was fully understood and implemented by the churches so that they could continue building a commonwealth of Christian communities in every civilization (the Early Christianity paradigm.)

But by the 4th century, the ambitions of men and their incessant need to harness everything into logical systems that could be wielded by bureaucracies, became the dominant attitude toward the church and its theology, toward government, and toward society, and ended up creating an institution so powerful and expansive that it would dominate Western Civilization’s understanding of itself for the next 1,700 years.

[And now for the dramatic conclusion where I tie it all together…]

So… that was my long introduction to explain how I arrived at my take on these “nativity protest art” displays which are popping up on the front lawns of Catholic churches across America.

It seems to me these art installation protests are just more of this same overlap of Christendom and governmental power structures. It’s the last gasp of the old paradigm, once again attempting to be relevant.

While they make a good point, I wonder if they actually accomplish anything substantial for the communities they claim to be concerned about? Or if they are really more about garnering influence for those engaging in the protests. Overall, their response amounts to a cocktail of benign political stance and public alignment with a particular ideological “team”, while giving a big middle finger to the governmental authorities against whom they are protesting. Sounds familiar doesn’t it? Like many, many cultural responses to things we don’t like?

It’s sort of the “Christian” version of saying “f—ck the man”, which is not actually a Christian response, but is definitely an American one. Our impulse to tell our opponents to “f—k off”3 is largely considered to be one of our fundamental rights as Americans. It’s the gift that keeps on giving.

[It’s a gift I’m given almost daily as I drive home from the train station here in the great traffic-ridden state of New Jersey. And it’s one of the reasons I stopped riding Citibikes in NYC. Because I was regularly tempted to pay that gift forward to herds of pedestrians ambling down the bike lanes as if they were their own personal bridle paths.]

However, our tendency to respond in these ways typically ends with one of two results. A “road rage” incident, where something or someone gets broken (or worse); or remaining squarely in the world of symbolic tokenism and its meaningless (but sometimes cathartic) gestures.

Perhaps the better question is how can churches engage in supporting those in their neighborhoods and communities in ways that actually address their needs, and then make the sort of sacrifices (real ones, not token ones) for the welfare of the people in their neighborhoods. Sacrifices that have appropriate, tangible results.

And what are the life patterns, habits, new sets of priorities, and the framework around which church communities should be shaping themselves in order to have the resources and capacity to make a real difference, even if it is on a small scale, locally? The type of real difference that when it is multiplied across a movement of church communities in a large city, or throughout a region, or even across a national landscape, becomes extremely significant.

Do we have to just follow along in the same institutional footsteps as our predecessors or are there grass roots opportunities that don’t necessarily engage at all with the current governmental and board room-based systems? Is it possible that Jesus’s original plan to shape a global family movement was actually designed to be effective in every era and every culture? And was never intended to be institutionalized?

Churches that are intent on remaining effective in this next paradigm of Christianity need to regain a one-minded participation in the plan and patterns that the early churches were originally shaped around (by the apostles), which created a movement of grass roots communities, who were networked together, and functioned within, across, and beyond the realm of institutional boundaries, cultural traditions, and national borders, because they understood that they were Jesus’s extended family network; and they took care of one another, and then out of that internal strength, worked together to seek the welfare of their communities, focusing on each neighborhood, one at a time, while simultaneously, rapidly expanding across the globe.

Scott Canion is based out of the NYC area and is part of the METRO equipping team, a network of leaders who are establishing churches that are families… patterned after Acts.

From The Churches of the First Century, by Jeff Reed

Yes, I avoided typing out the word f-u-c-k. Not because I’m afraid of the word, but because I didn’t want to interrupt the flow of my essay for those who might be too shocked to continue. It’s a word that is common in our American vernacular… or maybe that’s just the space I live in, being that I work in NYC. (I hear it daily.)

It is a word with a wide range of usages (I could write a whole other essay about its versatility) and we need to be able to talk about it without blushing or feeling like, just by verbalizing it or typing it, we are somehow invoking the forces of evil. The truth is the “f—k off” attitude is a lot more prevalent in our hearts (mine included) than we’d like to admit. Many people who would never allow such a word to pass their lips, still manage to express that sentiment regularly in other ways… aimed at people or situations we find troubling. (Particularly in our social media posts.)

I’m much more concerned with a “f—k off” heart attitude, than I am with the word being typed or verbalized.

One is just a symptom of the other.